The decline in cases at Uganda’s Anti-Corruption Court

10-10-18

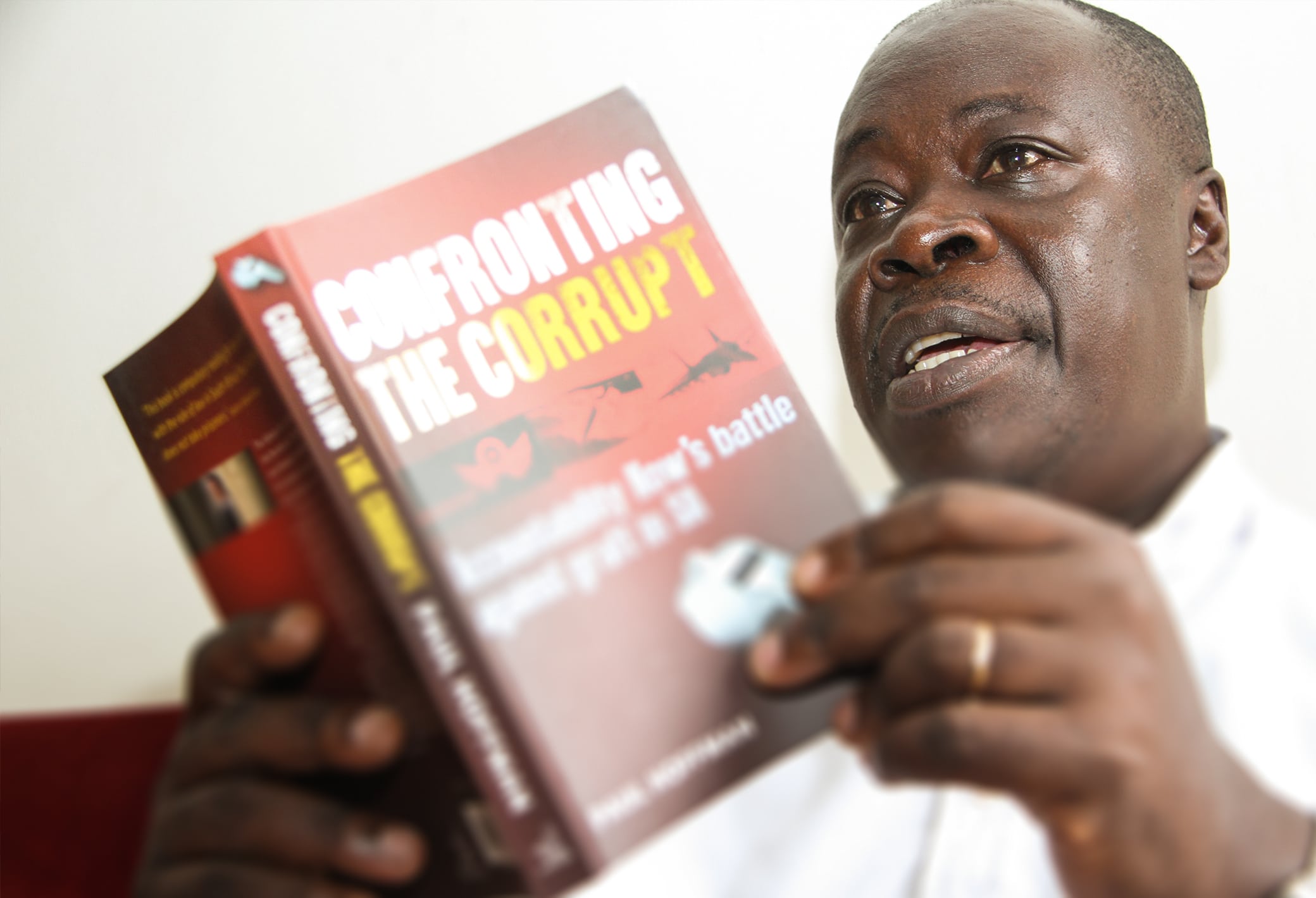

The number of cases filed at the Anti-Corruption Court in Uganda’s capital, Kampala is decreasing year by year. The Executive Director of the Anti-Corruption Court, Lawrence Gidudu regrets this development. Lawrence Gidudu coordinated the Ugandan side of Danida’s Law and Justice courses conducted in Denmark during a ten year period ending in 2015.

By Vibeke Quaade, Kampala

Look at this graph. Year after year, there is a decline in the number of cases that are brought before the Anti-Corruption Court, he says.

He then reads out the numbers behind the declining curve. In 2015, 321 cases were brought before the Anti-Corruption Court. In 2016, the numbers fell to 262. In 2017, it was 190. He pauses, takes a deep breath and exhales with a big, long sigh.

If we continue at this rate, there won’t be more than 130 cases this year. By 2019, we might be operating with fewer than 100 cases. It doesn’t make sense, he says.

Corruption on the rise

Lawrence Gidudu has been the Head of Uganda’s Anti-Corruption Court for five years. He is the third person to head the Court since it was established in 2008 as a special division of the High Court to adjudicate corruption and corruption related cases.

Lawrence Gidudu describes that when the Court was new in 2008, Uganda ranked as number 126 on Transparency International’s Global Corruption Perceptions index. The latest Transparency International ranking from 2017 lists Uganda as number 151 out of 180 countries. The judge lifts his eyes from the screen and leans back in his chair.

So, while the number of cases registered at the Anti-Corruption Court is falling, corruption continues to increase. It does not make sense; he repeats and shakes his head again.

Spreading like wildfire

Corruption in Uganda is generally considered a major obstacle to the country’s social and economic development. The judge explains that it affects a range of sectors and government institutions, including infrastructure, education, health, the judiciary and the police. It has also a severe negative effect on the delivery of public services.

Because of corruption, the low-income segments of society in particular do not get the services to which they are entitled, Lawrence Gidudu says.

The Ugandan government officially acknowledged a long time ago that corruption is the main challenge to the country’s general development. It has put in place reforms, laws and institutions to fight corruption including the Anti-Corruption Court. Despite the various instruments established to curb corruption, the vice seems to be spreading like wildfire.

Lawrence Gidudu offers an explanation.

Corruption has become part and parcel of the way the system works. Whether you belong to the poorer segments of the population or the more affluent minority, it is very hard to get anything done unless you subscribe to the corrupt ways. Controlling it has become almost impossible, he says.

The large complicated cases

Nevertheless, resolving and settling corruption cases brought to the Anti-Corruption Court are precisely what Lawrence Gidudu does. It is set up to operate as an orderly, expeditious, efficient and cost effective forum for adjudication of corruption and corruption related cases. Cases handled include embezzlement, causing financial loss, abuse of office, bribery, fraudulent false accounting, illicit enrichment, tax evasion and conflict of interest. Most of these crimes are committed through digital platforms, which require technologically advanced tools in investigations.

Setting a precedent

Since the court started in 2008, it has handled several such controversial cases, one of them being the so-called “Uganda vs Jimmy Lwamafa case”.

When Lawrence Gidudu took office in 2013, the “Uganda vs Jimmy Lwamafa case” was already underway. About a year later, it was handed over to him as the Head of the Court. The following year he completed it. He found three former top employees of the Ministry of Public Service guilty of swindling Shs 88.2 billion in a pension scam. It was after the “Uganda vs Jimmy Lwamafa” ruling that the number of cases brought before the Anti-Corruption Court began to drop. Lawrence Gidudu explains that in Uganda, it is rare to see top government officials convicted. Jimmy Lwamafa was a former Permanent Secretary and the most senior civil servant in the Ministry of Public Service. The verdict showed that the Anti-Corruption Court was ready to convict anyone regardless of his or her social status.

The case assured people that the Anti-Corruption Court was fair and objective, as it did not have any political or any other affiliations, Lawrence Gidudu says, looking pleased at the thought.

The user-friendly courts

However, an unwelcome side effect of this fair reputation has been a decline in the number of cases. Because top officials risk being charged for wrongdoing, they subsequently try to avoid having their cases tried at the Anti-Corruption Court. As Lawrence Gidudu remarks laconically,

The corrupt prefer more “user-friendly” courts.

Most of the cases handled by the Anti-Corruption Court are referred by the Uganda Revenue Authority, publicly renown for being strict in terms of sticking to the rules as Lawrence Gidudu puts it, and the Inspectorate of Government, also known as the IGG. The IGG is charged with the responsibility of eliminating corruption, the abuse of authority and of public office and has the power to investigate or cause investigation, arrest or cause arrest, prosecute or cause prosecution in cases involving corruption.

If it were not for the Inspectorate of Government and Uganda Revenue Authority we would have been out of business long ago, he says.

Nevertheless, Lawrence Gidudu believes that there are strong forces that find institutions like the Anti-Corruption Court an inconvenience, forces that want the institutions that work against corruption to crumble and be wiped off the map of Uganda and of the Uganda Judiciary.

It’s absurd, everyone knows that corruption is at an all-time high and here we are with the Anti-Corruption Court struggling to exist to be able to curb the wise, he says.

Vibeke Quaade, Communications Consultant, Danida Fellowship Centre.

Go back to our stories